Stories...

L2L1 Diagnostic Scenarios: Where Your Executive Identity is Truly Tested

The Real-life Scenarios Every Multilingual Leader Fails (Until They Don’t)

Most leaders speak their second language perfectly well… until something difficult happens.

That’s why the L2L1 Assessment does not test vocabulary, grammar, or fluency. It tests something much more important:

How much of your leadership identity survives under pressure in L2.

Here are some of the scenarios that reveal the truth instantly:

🔥 High-Pressure

• A board member interrupts you mid-sentence • An investor challenges your numbers aggressively • You must explain a complex idea without notes • A client becomes emotional or confrontational

🧠 Cognitive Stress

• Translating jargon on the fly • Thinking fast during rapid-fire Q&A • Keeping structure while processing two languages

🎭 Identity Drift

• Disagreeing with a senior peer without sounding blunt • Showing empathy without over-apologising • Maintaining humour, warmth, and authority at the same time

🌍 Cross-Cultural Agility

• Managing a group call with 6 accents • Handling sarcasm or irony • Leading a discussion where no one shares your cultural baseline

These scenarios form the backbone of the Identity Mapping™ process — and they reveal, with brutal clarity:

“Where do you lose yourself when you switch languages?”

When leaders see their scenario results side-by-side (L1 vs L2), the shift is often shocking.

And then liberating.

Because once the identity drift is visible, we can rebuild it.

L2L1 doesn’t teach you better English. It gives you back your executive self when you speak it.

#L2L1 #ExecutiveIdentity #ExecutivePresence #MultilingualLeadership #CorporateHumor #LeadershipCommunication #CrossCulturalLeadership #ExecutiveCoaching #LanguagePerformance #IdentityTransfer #Duolingo?

Stories...

Beyond Fluency: Why “Speaking a Foreign Language” Is No Longer Enough

The outdated badge of honour

For years, “fluent in English / French / Spanish / Esperanto” was the golden line on every CV. It meant international exposure, intelligence, and adaptability.

But in 2025, it’s everywhere. Everyone claims fluency. Everyone studied abroad, watches Netflix in English, or works in global teams.

And yet — true mastery remains rare. 👉 Only 28 % of EU adults who speak a foreign language say they are actually proficient in it (Eurostat). 👉 According to YouGov, in the UK, just 1 in 5 Britons say they can hold a full conversation in another language (if ordering a beer in a pub qualifies as 'a full conversation'...).

Meanwhile, OECD data show that over 50 % of vacancies for managers and professionals in the EU/UK require a foreign language beyond the native one — and that those jobs pay more.

So “fluent” is no longer a differentiator. It’s the entry ticket. But is it enough?

The illusion of competence

Fluency is about vocabulary. Professional credibility is about authority, rhythm, and emotional precision. You can be fluent and still:

lose authority under pressure,

misread tone or humour,

flatten your personality to “fit in.”

come home mentally drained from spending a whole day working in L2

As one recent academic study of multilingual professionals noted: “Even when participants spoke several languages, they reported feeling less able to express themselves fully in formal corporate interactions.” (MDPI, 2024)

The real challenge: Language as leadership

Today’s leaders don’t just switch languages — they know how to stay confident, credible, and culturally agile whether they’re presenting in Paris, pitching in New York, or negotiating in Dubai.

The next frontier: Executive Identity in L2

Traditional teaching stops at fluency. Real transformation begins where fluency ends — when you can project the same clarity, warmth, and command in your second language as in your first.

Because when you speak your L2, the question isn’t “Am I fluent?” It’s “Am I still me?”

More stories...

The Hidden Handicap No One Talks About at the Top

It’s one of the best-kept secrets of global leadership: many C-suite executives lose power the moment they switch language.

Not because they lack vocabulary. Not because of grammar mistakes. But because they lose the voice that built their authority.

A CEO who commands a boardroom in Paris or Frankfurt can sound hesitant in English — softer tone, less humour, fewer pauses of control. The message lands weaker, the leadership signal blurs.

This isn’t about translation. It’s about identity transfer. When language changes, so does rhythm, confidence — even perceived intelligence.

The cost is invisible but real: missed opportunities, diluted investor calls, cautious media exposure, and growing dependence on “native” intermediaries who filter both message and intent.

And yet… What to do about it? Where to turn? Who to even confess this secret to? Is it incurable? I'm mentally exhausted!

Worse still: HR’s well-meaning solution — “Let’s book you 30 hours of private English lessons!” — often makes it worse. Because this isn’t a language problem. It’s a leadership problem expressed through language.

Politicians face it under the spotlight; executives suffer it behind closed doors. But once you name it, you can fix it — not with more grammar, but with a method that restores authority, authenticity, and agility in your second language.

Image: “The Executive Who Lost His Voice” — because even Louis de Funès knew that comedy and tragedy are separated by one misplaced word.

An Experience

L1 Offense -L2 Defense

Top-tier French executive. Fine strategist. Natural presence. Brilliant speaker in her L1. Her subtlety, precision, and mastery of nuance were an integral part of her exceptional executive package.

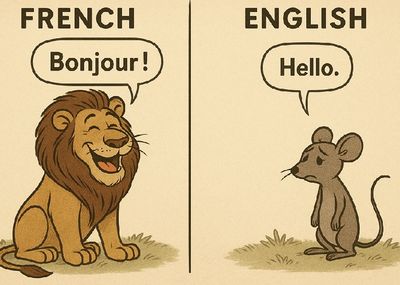

In French, she is a lion. Stable posture. Fast decisions. Offensive intelligence. She dominates without forcing. She attacks issues directly, cuts through complexity, leads momentum.

In English, she shifts into defensive mode. She protects herself more than she expresses herself. She avoids mistakes before she carries her ideas.

Her L2L1 profile: The Diplomat A profile built on nuance, subtlety, and relational precision. Powerful in L1. But highly vulnerable in L2, where excess sophistication weakens impact.

The L2L1 Diagnostic

First step: verify the fundamentals. The outcome was unambiguous:

✅ No comprehension issues — one-to-one, conferences, Zoom ✅ Vocabulary fully sufficient to deliver all strategic content ✅ No technical weakness in English

👉 The problem was neither language nor intelligence.

What we identified:

- Constant over-justification

- Loss of speed under pressure

- Unconscious self-censorship

- A drop in perceived authority

And most critically, this key mechanism:

👉 The permanent attempt to recreate in English the French “subjunctive of the conditional”:

“I would maybe suggest that we could possibly consider…”

Where English expects:

“My recommendation is clear: we do X.”

What Happens Internally

In L1, she operates in action mode. In L2, she shifts into protection mode.

Her intelligence does not disappear. Her posture changes:

- From attack ➝ to avoidance

- From leadership ➝ to caution

- From impact ➝ to justification

Result: 👉 Loss of confidence 👉 Mental fatigue 👉 Deep identity dissonance

Consequences for Her Career and Her Company

In French: a natural leader. In English: perceived as cautious, sometimes hesitant.

Yet:

- Strategic decisions are made in English

- Boards are international

- Investors judge in English

This gap became a strategic risk for:

- Her credibility

- Her career trajectory

- Her company’s effectiveness

What L2L1 Worked On

Not the language. But the reconstruction of her executive authority in English:

✅ High-intensity role-playing ✅ Radical message simplification ✅ Reprogramming her thinking architecture in L2

Objective: 👉 Stop translating her French power 👉 Think, decide, and attack directly in English

The lion was never gone. It was simply being restrained by the language.

Thinking in a foreign language is... a MYTH

And worse: it is handicapping and identity-distorting.

Here is a simple test.

Think of a foreign language you use professionally. Now ask yourself:

Are you focused on what you want to say — or on monitoring how you are saying it? Are you listening to yourself? Are you hearing yourself?

The idea that language mastery begins when you think in a foreign language is deeply misleading.

Inner speech proves nothing. It has no audience, no timing pressure, no social cost. You can think imprecisely, awkwardly, even incorrectly — and still feel fluent.

But that habit comes at a price.

When you are busy “thinking in a foreign language”, you are no longer thinking about content. You are managing form. You are translating yourself. Or Trying.

That creates a cognitive handicap:

- ideas arrive later

- arguments lose sharpness

- spontaneity disappears

- authority weakens

And over time, it creates something more damaging: identity distortion.

You stop sounding like yourself. Not because you lack vocabulary — but because your attention has shifted away from meaning, intent, and positioning, toward self-surveillance.

True mastery shows up much later, and in a very different way.

It begins when you stop listening to yourself and start hearing the language.

Not grammar rules — but signals:

- sentences that are correct yet feel wrong

- tones that miss their social mark

- word choices that dilute authority rather than carry it

At that point, the language has internalised standards, not rules. Your ear becomes more demanding than your conscious knowledge.

This is also why highly proficient multilinguals often feel less comfortable than intermediate speakers: they hear distortions others do not.

At L2L1, we use this distinction as a diagnostic lens.

Not to test fluency, but to observe where attention sits: on content or on self-monitoring, on intent or on form, on authority or on control.

Let us do the listening. You do the talking.